Dharamshala:- Our decision to take the controversial new train from Xining to Lhasa in 2012 tugged at my conscience, but it was the one way that we could logistically manage our trip to Tibet. And I will admit that the opportunity to watch the vast Tibetan plateau unfold before our eyes was a compelling prospect.

Dharamshala:- Our decision to take the controversial new train from Xining to Lhasa in 2012 tugged at my conscience, but it was the one way that we could logistically manage our trip to Tibet. And I will admit that the opportunity to watch the vast Tibetan plateau unfold before our eyes was a compelling prospect.

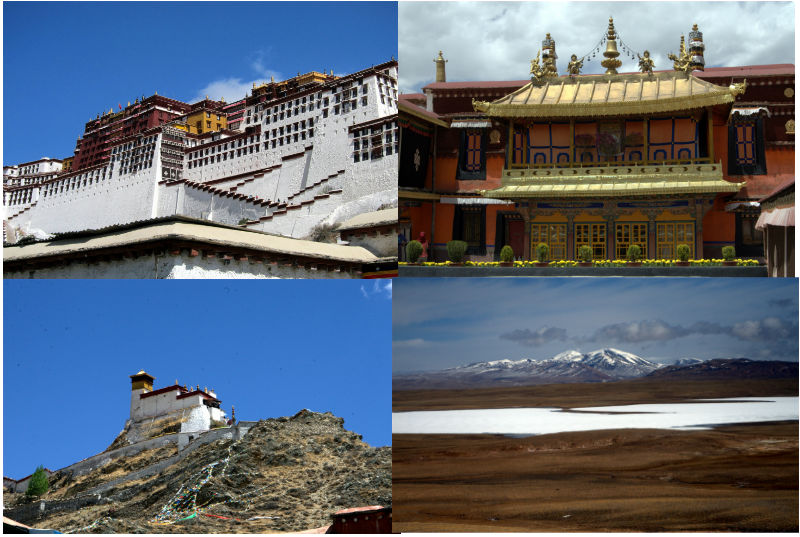

My husband and I board at Xining in the evening and are soon travelling in darkness, but we wake up the next morning to magnificent scenery. Welcome to Tibet, the Land of Snows. Vast brown plains stretch in every direction with smooth snow-covered mountains on the horizon. Occasionally there is a lake or stream, usually frozen. All under brilliant sunshine. I find it starkly beautiful, and love that there is such wild, wide open space left in the world. We see some small settlements, or more often, just a house sitting alone. Sometimes there is a person or two looking after a herd of yaks or sheep.

As we approach Lhasa, the settlements grow larger and, with a slight decrease in elevation, the terrain becomes rockier and seemingly more fertile. Several villages are ringed by stone-walled garden plots and yaks drag ploughs over the land. We see many military vehicles heading towards Lhasa as we get closer, at one point counting a convoy of 70 army trucks. Tibet is indeed the problem child of China.

The train pulls into Lhasa almost 24 hours after leaving Xining. As we leave the station, we are immediately singled out as foreigners and subject to police escort. We are taken to our prearranged guide who works through some paperwork with the police officer, and are finally released. At the time of our visit, foreigners are not allowed to travel independently in Tibet. We can walk around town on our own but need to have our passports and papers with us at all times in case we are checked. Most importantly, our guide instructs us to take absolutely no photos of police or military personnel. This could be challenging as there are armed police with surveillance cameras perched on building rooftops, and simply police and security everywhere you look, often marching through town in squadrons.

On our way into town, we see the Potala Palace for the first time and it is a staggering sight. All the photos I’ve seen have not prepared me for the beauty and scale of this incredible structure. The next day we have an opportunity to tour the inside on a closely timed and regulated visit. A few monks can be spotted in the Potala Palace but we wonder about their authenticity as we have been told they are all actors and spies. The present building, dating from 1645, was the religious and political centre for Tibet and the home of successive Dalai Lamas. It is now essentially a museum, with limited rooms open to the public. Nonetheless we can’t help but be excited about what we are seeing … huge jewel-encrusted tombs of several Dalai Lamas, statues and thangkas depicting Buddhas, protectors and gods, all exhibiting riotous colour.

We also spend time in the Barkhor, Lhasa’s medieval town centre and marketplace, the spiritual heart of Lhasa for Tibetans. This is where the Jokhang, Tibet’s holiest temple, is located. Pilgrims perform kora around the temple and the maze of old streets surrounding it. We join the shuffling throngs and it feels fascinating to watch and be part of this ancient ritual of pilgrimage. Later we browse the small shops and stalls that sell everything from yak butter and cheese to clothing for monks to prayer wheels and prayer books. There are shops that sell brightly painted furniture and others with containers for storing tsampa. Merchants trade the highly valued caterpillar fungus which is found in Tibet and used in traditional medicine.

One of the things I love about Tibet is the obvious love for beauty and the arts. Even objects with the most mundane function are beautifully crafted, painted, carved, or otherwise made to be aesthetically pleasing. Pilgrims from the countryside have their hair coiled into ropes, wrapped around their heads and decorated with coral, turquoise, and brightly coloured wool.

We are in Tibet for a full week and for much of our time there we feel like we are on sensory overload. We gain tantalizing glimpses of Tibet’s rich culture, artwork, and architecture, while grappling with the idea of continual security and surveillance. Perhaps the most poignant moment for us came as we walked down the darkened corridors of one monastery looking at 300-year-old thangkas. We shone lights on them to see the stories of Buddhism and Tibetan history. Some of the paintings still had remnants of old newspapers glued on top of them, left over from the Cultural Revolution when monks tried to save these precious artworks from being destroyed. I am so glad they survived, and I am confident that likewise the spirit and culture of Tibetans will survive and flourish.

![Tibet has a rich history as a sovereign nation until the 1950s when it was invaded by China. [Photo: File]](/images/stories/Pics-2024/March/Tibet-Nation-1940s.jpg#joomlaImage://local-images/stories/Pics-2024/March/Tibet-Nation-1940s.jpg?width=1489&height=878)